Reviewed for NetGalley.

* * * * *

* * * * *

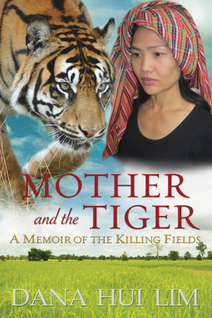

Dana Hui Lim, tells her real life story of the “Killing Fields” in Mother and the Tiger. Lim was just a small child when the Vietnam War spilled over the border into Cambodia, where she lived with her parents and siblings in the village of Kratie. Shortly thereafter, four young men burst into her family’s home, giving them mere minutes to collect their things. The soldiers sought no explanations, only obedience. Young Dana and her family joined the march from their village, watching as hospitals were emptied and people carried away their sick relatives. The soldiers’ message was clear: those too old or sick to keep up were shot and left on the roadside. They fired their weapons over the heads of the villagers to keep the crowd moving, literally marching many to their death. The soldiers, peasant youths of at most twelve to thirteen years of age, according to Lim, called themselves the “Khmer Rouge.” (Khmer was the term the Khmer people used to refer to Cambodia.) Year “zero” of the new Cambodia, had begun.

Following Lim through the tragedies of her early years may leave one to dub her a “survivor,” and so she is—but she is so much more. Believing that it is important for Cambodians to tell their story for the sake of history, so that those stories are not lost, Lim leaves no stone unturned. She finds the exercise essential, believing her tale will “serve as a warning to people of all nations and races to be wary of the danger that can occur when ideology is not subjected to reason.” Lim speaks of the death, the fear and terror, and the evil of a regime that did not value human life. “War,” she says, “is inevitable when insane leaders are permitted to take power, and then those who could make a difference choose to look the other way.” She goes on: “We were to be guided by a gentle leadership that would usher in a glorious new age, one where all would be equal and all would work for the common good.” It is a shocking truth that the deaths of untold millions in the 20th century, many in Cambodia, were attributable to just that ideology.

In Mother and the Tiger, Lim introduces her family members, complete with all their foibles and idiosyncrasies. Take her mother, for example, who was brave enough to face down a tiger in the jungle, armed with nothing more than a burning stick of wood, so as to save her family, but who also was able to—and did—give her children away to others on more than one occasion. (Apparently, this was not unusual in Cambodia.) In the end, Lim found a new country, an education, and eventually, freedom. “For the first time in my life,” she says, “no one could tell me what to do.” After some years, she returned to her homeland where she toured a museum dedicated to educating others about the killing fields. Having surmised that the other museum visitors thought themselves “lucky that nothing like this could happen where they came from,” she leaves readers with a caution. “They are wrong, of course,” she says. They are “just lucky that a person with the right combination of charisma and madness [has] never come to power in their country.” Think of that the next time you go to exercise your right to vote. It is not a popularity contest—it is a sacred right—and it should be treated as such.

Following Lim through the tragedies of her early years may leave one to dub her a “survivor,” and so she is—but she is so much more. Believing that it is important for Cambodians to tell their story for the sake of history, so that those stories are not lost, Lim leaves no stone unturned. She finds the exercise essential, believing her tale will “serve as a warning to people of all nations and races to be wary of the danger that can occur when ideology is not subjected to reason.” Lim speaks of the death, the fear and terror, and the evil of a regime that did not value human life. “War,” she says, “is inevitable when insane leaders are permitted to take power, and then those who could make a difference choose to look the other way.” She goes on: “We were to be guided by a gentle leadership that would usher in a glorious new age, one where all would be equal and all would work for the common good.” It is a shocking truth that the deaths of untold millions in the 20th century, many in Cambodia, were attributable to just that ideology.

In Mother and the Tiger, Lim introduces her family members, complete with all their foibles and idiosyncrasies. Take her mother, for example, who was brave enough to face down a tiger in the jungle, armed with nothing more than a burning stick of wood, so as to save her family, but who also was able to—and did—give her children away to others on more than one occasion. (Apparently, this was not unusual in Cambodia.) In the end, Lim found a new country, an education, and eventually, freedom. “For the first time in my life,” she says, “no one could tell me what to do.” After some years, she returned to her homeland where she toured a museum dedicated to educating others about the killing fields. Having surmised that the other museum visitors thought themselves “lucky that nothing like this could happen where they came from,” she leaves readers with a caution. “They are wrong, of course,” she says. They are “just lucky that a person with the right combination of charisma and madness [has] never come to power in their country.” Think of that the next time you go to exercise your right to vote. It is not a popularity contest—it is a sacred right—and it should be treated as such.