Thank you, NetGalley, for the opportunity to read and review Ravensbruck.

* * * * *

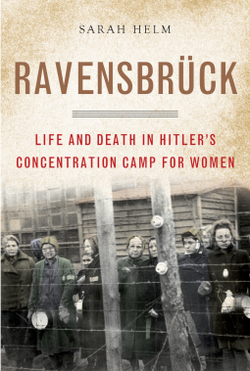

I recently finished reading Ravensbruck: Life and Death in Hitler’s Concentration Camp for Women, by Sarah Helm. I had to put it down for a couple of weeks afterward before I could gather my thoughts sufficiently well to write a review. I found this read both profoundly insightful and deeply disturbing.

I’ve read a lot of books about WWII, the Nazi regime in general, and of the concentration camps in particular. The stories Helm shares, charged with emotion, are real. I could nearly smell death as I worked my way through. I can only wonder how long that stench hung over Europe after the war ended. The sheer number of murders and of the resulting piles of bodies—or in some cases, of ashes—is mind-boggling.

WWII, like all the “great” wars of the 20th century, was an ideological one—not a religious one—witnessed by the fact that the Nazis victimized Jews, Christians, Poles, the French, “a-socials,” gypsies, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and so many, many more . . . The weapons they used included those expected, as well as those I’d never read of before, namely, the mobile gas chambers.

One of the things that stood out for me with Ravenstruck, is that Helm managed to capture the personalities of some of those in charge in a way that left me shaking my head. When she shared Heinrich Himmler’s fascination with breeding chickens, or the details of his notes with his wife, he sounded so different from the beast that oversaw evil on such an unimaginable scale. When Helm set out the background of “normal” young women, turned to killer guards, I was left speechless.

From whence does such evil come? How could it survive long enough to do what it did during these days? Why did those who knew about it, do nothing about it, rather than take whatever action was necessary to stop it? That “hate” could take root and grow to such levels is shocking. In this regard, Helm also shared the intellectual dishonesty, the irrationality necessary for people to create such a system, to grow it, and to fight for it to continue.

It is a shocking reality that some would repeat those times, as our daily newscasts witness. There are people today who want to wipe out those whose ideas and way of life do not match up ideologically with their own. I recall the famous Edmund Burke quote: “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” Therein came the real difficulty for me when I read Ravensbruck—I was left with a deep appreciation for how much we require strength and truth and moral clarity in leadership though, I daresay, the world is struggling to find it.

* * * * *

I recently finished reading Ravensbruck: Life and Death in Hitler’s Concentration Camp for Women, by Sarah Helm. I had to put it down for a couple of weeks afterward before I could gather my thoughts sufficiently well to write a review. I found this read both profoundly insightful and deeply disturbing.

I’ve read a lot of books about WWII, the Nazi regime in general, and of the concentration camps in particular. The stories Helm shares, charged with emotion, are real. I could nearly smell death as I worked my way through. I can only wonder how long that stench hung over Europe after the war ended. The sheer number of murders and of the resulting piles of bodies—or in some cases, of ashes—is mind-boggling.

WWII, like all the “great” wars of the 20th century, was an ideological one—not a religious one—witnessed by the fact that the Nazis victimized Jews, Christians, Poles, the French, “a-socials,” gypsies, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and so many, many more . . . The weapons they used included those expected, as well as those I’d never read of before, namely, the mobile gas chambers.

One of the things that stood out for me with Ravenstruck, is that Helm managed to capture the personalities of some of those in charge in a way that left me shaking my head. When she shared Heinrich Himmler’s fascination with breeding chickens, or the details of his notes with his wife, he sounded so different from the beast that oversaw evil on such an unimaginable scale. When Helm set out the background of “normal” young women, turned to killer guards, I was left speechless.

From whence does such evil come? How could it survive long enough to do what it did during these days? Why did those who knew about it, do nothing about it, rather than take whatever action was necessary to stop it? That “hate” could take root and grow to such levels is shocking. In this regard, Helm also shared the intellectual dishonesty, the irrationality necessary for people to create such a system, to grow it, and to fight for it to continue.

It is a shocking reality that some would repeat those times, as our daily newscasts witness. There are people today who want to wipe out those whose ideas and way of life do not match up ideologically with their own. I recall the famous Edmund Burke quote: “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” Therein came the real difficulty for me when I read Ravensbruck—I was left with a deep appreciation for how much we require strength and truth and moral clarity in leadership though, I daresay, the world is struggling to find it.