I received a copy of The Nightmare Dance: Guilt, Shame and the Holocaust, by David Gilbertson, from Netgalley. In exchange, I offer this, my fair and honest review.

* * * * *

David Gilbertson opens The Nightmare Dance with an introduction into the changes in Poland and other hard hit places during WWII, with a caution against the commercialism that has sprung up in the Auschwitz area. Though millions visit regularly, the trek is a spiritual experience for only a few. For many others it is little more than a stop on the travelers’ agendas. Gilbertson’s caution should be taken seriously. While many think the horrors of the WWII era were an historical aberration, in fact, we see some of the evil of which man is capable, play out in the evening news on a daily basis.

From whence does such hatred as could birth the concept of, and the program for, the Final Solution come? I can only imagine . . . (and that, not very well).

There are many lessons to take from these readings: lessons about the dangers of placing “blame” on any group at any time, for any reason; lessons about the power of language and propaganda; lessons about the cost of denying truth (so as to enjoy a free and easy conscience). Gilbertson lays these out through his renditions of European history regarding the Jews, with information regarding the position of the organized Church from time to time, and of the German laws that came about prior to the Holocaust. Presumably, their goal was to make it easier for some to see others as expendable. Sadly, that goal was met.

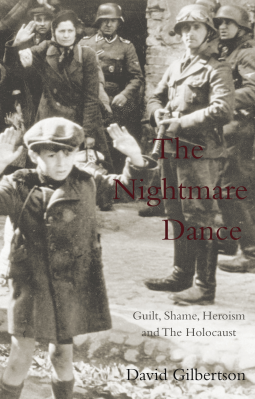

The horror of the concept of the Final Solution is profound. The number of people that had to turn a blind eye in order for tens of thousands of others to disappear from an area—sometimes within days—is startling. The entire idea that there could be “blind prejudice and passionate hatred” is confusing. Yet, from the information Gilbertson provides about Osjakow, the death of a shtetl, to the story of the unnamed boy in a photograph taken in Warsaw, to the details of life in the Jewish ghettos, to the life story of Stella Goldschlag who turned in her own, the information in The Nightmare Dance, is all worth reading and remembering. So too, is the story of King Christian X of Denmark and the Danish people who did all they could to save others, and the story of Janusz Korczak who, though unable to save the children in his care, did all he could to bring them a measure of peace during their short lives. The truths of history can only guide us if we face them, and so, I highly recommend this (dark and difficult) read.

* * * * *

David Gilbertson opens The Nightmare Dance with an introduction into the changes in Poland and other hard hit places during WWII, with a caution against the commercialism that has sprung up in the Auschwitz area. Though millions visit regularly, the trek is a spiritual experience for only a few. For many others it is little more than a stop on the travelers’ agendas. Gilbertson’s caution should be taken seriously. While many think the horrors of the WWII era were an historical aberration, in fact, we see some of the evil of which man is capable, play out in the evening news on a daily basis.

From whence does such hatred as could birth the concept of, and the program for, the Final Solution come? I can only imagine . . . (and that, not very well).

There are many lessons to take from these readings: lessons about the dangers of placing “blame” on any group at any time, for any reason; lessons about the power of language and propaganda; lessons about the cost of denying truth (so as to enjoy a free and easy conscience). Gilbertson lays these out through his renditions of European history regarding the Jews, with information regarding the position of the organized Church from time to time, and of the German laws that came about prior to the Holocaust. Presumably, their goal was to make it easier for some to see others as expendable. Sadly, that goal was met.

The horror of the concept of the Final Solution is profound. The number of people that had to turn a blind eye in order for tens of thousands of others to disappear from an area—sometimes within days—is startling. The entire idea that there could be “blind prejudice and passionate hatred” is confusing. Yet, from the information Gilbertson provides about Osjakow, the death of a shtetl, to the story of the unnamed boy in a photograph taken in Warsaw, to the details of life in the Jewish ghettos, to the life story of Stella Goldschlag who turned in her own, the information in The Nightmare Dance, is all worth reading and remembering. So too, is the story of King Christian X of Denmark and the Danish people who did all they could to save others, and the story of Janusz Korczak who, though unable to save the children in his care, did all he could to bring them a measure of peace during their short lives. The truths of history can only guide us if we face them, and so, I highly recommend this (dark and difficult) read.