I received a copy of Hitler's Last Witness, by Rochus Misch, from NetGalley. In exchange, I offer this, my fair and honest review.

* * * * *

* * * * *

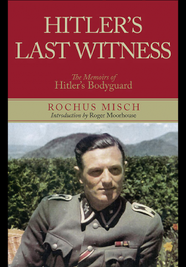

Few people had ready access to the Fuhrer, Adolph Hitler. Few who did lived to tell stories of the man and his actions from the inside. Rochus Misch, a member of Hitler’s staff and later, in charge of the telephones where Hitler stayed from time to time, was the last surviving member of this small group.

Misch tells his story of how he came to his position. He insists throughout that he knew nothing, and heard nothing, of the millions of deaths in the concentration camps while serving Hitler. Indeed, he writes that he only ever saw one report on the camps, and that from an International Red Cross report that “contained nothing disturbing.” At the outset, I found this idea . . . highly difficult to believe. Yet, when I read Misch’s story, I found he was able to reiterate the smallest of details of Hitler’s daily life and moves, yet he seemed rather uninterested in larger affairs. His concerns were simply to “do his job” for the Third Reich, and not to cross any lines that might get him in trouble as he had seen others do, only to find themselves on the front line—or killed. He barely noticed when a colleague “went away” (which meant he went to a concentration camp or was sent to the front). One example was of a guard who, failing to keep a mosquito from Hitler, was sent packing. For his part, Misch stuck to the rules. He wouldn’t even dance with Eva Braun when Hitler was away and she threw a spontaneous party, because “she was the Fuhrer’s girl.”

It was the little details of Germany before and during WWII, of the lives of Hitler and his associates that I found most intriguing in this read. I noted Misch’s descriptions of the places where they stayed, of the people and personalities of Hitler and his associates, and the “rules” the staff followed so as not to bother “the boss” (such as not to wear boots that made “deep impressions on the thick carpet”). (Really?)

Risch met Hitler’s siblings (and half-siblings), Eva Braun, and so many others. He tells of how Hitler and Eva Braun acted publicly (that he never saw any intimacies between them, nor did his colleagues) and of their last hours together when the two were married. Does it matter to anyone that Hitler knew all his staff on sight and by name, or that he had a “first-class” memory, or that he rarely showed anger? Does it matter that he knew who would attend a dinner? That he never carried a weapon or that those who surrounded him often did—and that it seems he had no fear of that? Does it matter that Misch never saw Hitler laugh out loud? That the Fuhrer had a favorite dog—Blondie—who performed tricks for him? That he joked about always being the last to know anything that was going on around him? That he had poor vision, but did not want others to know because he thought it showed weakness? Does it matter that we know the type of car Hitler preferred to ride in? Or that he liked to bowl or to watch films? Perhaps not. From an historical perspective, Hitler is a monster. But Misch’s account does show that even monstrous people are—people. This “humanizing “ does not make Hitler a sympathetic character, but it does show me what people can be capable of doing.

Misch tells his story of how he came to his position. He insists throughout that he knew nothing, and heard nothing, of the millions of deaths in the concentration camps while serving Hitler. Indeed, he writes that he only ever saw one report on the camps, and that from an International Red Cross report that “contained nothing disturbing.” At the outset, I found this idea . . . highly difficult to believe. Yet, when I read Misch’s story, I found he was able to reiterate the smallest of details of Hitler’s daily life and moves, yet he seemed rather uninterested in larger affairs. His concerns were simply to “do his job” for the Third Reich, and not to cross any lines that might get him in trouble as he had seen others do, only to find themselves on the front line—or killed. He barely noticed when a colleague “went away” (which meant he went to a concentration camp or was sent to the front). One example was of a guard who, failing to keep a mosquito from Hitler, was sent packing. For his part, Misch stuck to the rules. He wouldn’t even dance with Eva Braun when Hitler was away and she threw a spontaneous party, because “she was the Fuhrer’s girl.”

It was the little details of Germany before and during WWII, of the lives of Hitler and his associates that I found most intriguing in this read. I noted Misch’s descriptions of the places where they stayed, of the people and personalities of Hitler and his associates, and the “rules” the staff followed so as not to bother “the boss” (such as not to wear boots that made “deep impressions on the thick carpet”). (Really?)

Risch met Hitler’s siblings (and half-siblings), Eva Braun, and so many others. He tells of how Hitler and Eva Braun acted publicly (that he never saw any intimacies between them, nor did his colleagues) and of their last hours together when the two were married. Does it matter to anyone that Hitler knew all his staff on sight and by name, or that he had a “first-class” memory, or that he rarely showed anger? Does it matter that he knew who would attend a dinner? That he never carried a weapon or that those who surrounded him often did—and that it seems he had no fear of that? Does it matter that Misch never saw Hitler laugh out loud? That the Fuhrer had a favorite dog—Blondie—who performed tricks for him? That he joked about always being the last to know anything that was going on around him? That he had poor vision, but did not want others to know because he thought it showed weakness? Does it matter that we know the type of car Hitler preferred to ride in? Or that he liked to bowl or to watch films? Perhaps not. From an historical perspective, Hitler is a monster. But Misch’s account does show that even monstrous people are—people. This “humanizing “ does not make Hitler a sympathetic character, but it does show me what people can be capable of doing.